The mythic tale of Pandora’s Box often comes to mind through my Leadership Formation work.

The mythic tale of Pandora’s Box often comes to mind through my Leadership Formation work.

In Greek mythology Pandora is the first woman. Created by Hephaestus and Athena, who in concert with other deities endowed her with many unique gifts. (Interestingly Pandora translates from Greek as ‘all-gifted’.)

Various traditional renditions tell how Pandora’s curiosity drew her into opening a forbidden box thus releasing all the evils contained within it out into the world – famine, disease, sickness, burdensome toil and myriad other pains. Realising her mistake she quickly closed the box. Only Hope remained trapped inside.

For me, this is not a completely satisfying story. I see parallels to the Biblical story of Eve, where the woman succumbs to temptation and brings evil to an innocent world. Reflecting on our modern world it’s difficult to argue for this theme. Far more trouble appears to be caused by the acts of men!

I want to consider this myth in a different way. As with Pandora, I believe we are each created with unique potentials and gifts. Unfortunately we often experience poor conditions for the development of these deep potentials, especially through childhood.

As Karen Horney writes, instead we each build an idealised image of who we should become. I can envisage this as a kind of mental ‘box’ we lock ourselves into; with rigid patterns of thinking and behaving; full of compulsions, conflicting drives and false solutions all attempting to grant safety in a hostile world.

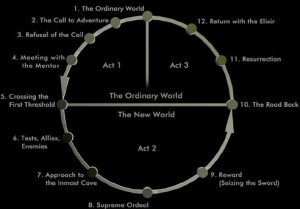

To grow into our human potential requires each of us to look within the interior ‘box’ we have constructed. Like Pandora, the initial motivation may be curiosity. However many may come from a more painful place; unhappiness or even desperation.

To me the image of ‘opening the box and releasing evils’, refers to the psychological process of confronting our inner conflicts and fears.

Opening the box entails danger to the individual.

Once the box is opened and the ‘evils’ are released, they cannot be forced back into the box. Once these evils are brought into full view, they are in our consciousness for all time. We can either try to create yet another box to contain them i.e. another layer of neurosis; or we can face up to these evils and begin the struggle of growing into our real potential and happiness.

The Ancients were astute in identifying Hope as the saving grace. Hope being the desire and confidence to search for a future good which is difficult but not impossible to attain. Hope gives each of us the strength to persevere in the face of adversity.

Pandora was not the cause of the worlds ills.

I view Pandora as an archetypal seeker of inner truth, confronting her fears in order to realise her gifts and potential. Wise Pandora offers clear guidance for our own inner work.

Our silkworms are spinning their cocoons, readying to make the great leap from two inch caterpillar to delicate white moth.

Our silkworms are spinning their cocoons, readying to make the great leap from two inch caterpillar to delicate white moth.